Source: Could Macron and Brexit make Paris Europe’s tech capital?

FRANCE 24

Could Macron and Brexit make France Europe’s tech capital? 🇫🇷

Date created : Latest update :

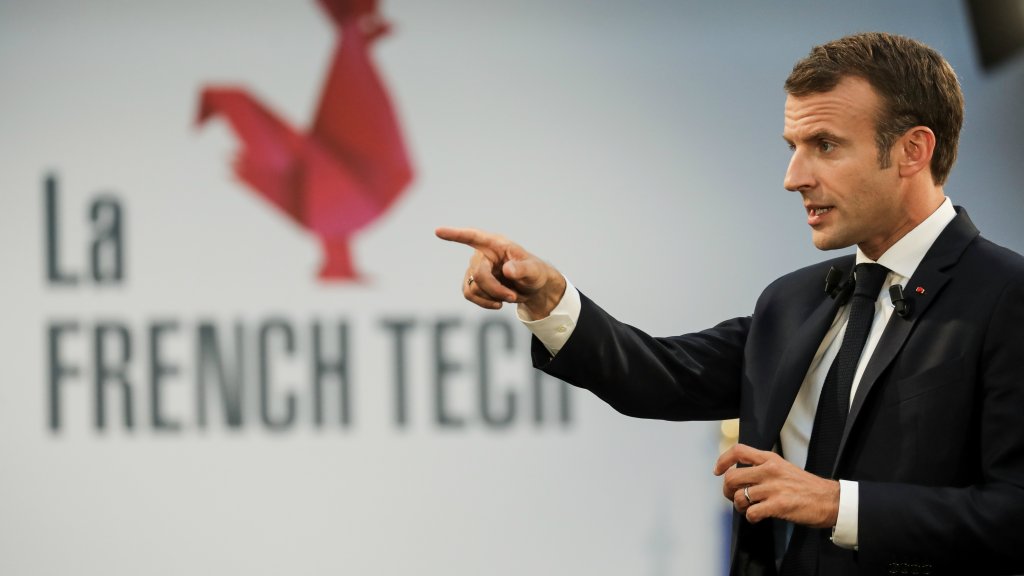

Shortly after his election in May 2017, President Macron said he wanted France itself “to think and move like a start-up” – a vision of the country’s digital future that is gaining traction as Britain wrestles with Brexit.

French President Emmanuel Macron’s vow to make France a ‘start-up nation’ amid the uncertainty over Brexitis raising the question of whether Paris could supplant London as the capital of European tech.

Since his election, Macron has wooed tech entrepreneurs with a string of initiatives in the form of lavish tax breaks, subsidies, and credits for research. In March 2018, he promised to invest €1.5 billion into artificial intelligence research through 2022.

Some of these initiatives, in addition to Macron’s dynamism, have lured British tech companies who are looking to gain a foothold in Europe.

“It made sense to have a European base,” said Cedric Jones*, a Briton who recently launched a start-up at Station F, the cavernous old train station that is now home to the world’s largest start-up campus. “If I’m going to make waves in continental Europe… I wanted to get here before Brexit happened.”

Jones is among dozens of foreign entrepreneurs who have recently launched their start-up at Station F, whose 3,000 desk hub has seen spiraling applications from English-speaking nationals in the last two years.

Some cite political woes back home, the burgeoning French tech sector, or are inspired by Macron’s bid to make Paris the innovation heart of Europe.

“There’s an air of optimism and a can-do spirit in France that I feel we’ve lost somewhat in the US,” said Mark Heath, a New Yorker, who stayed on in France to launch a start-up after studying at INSEAD in 2017.

The Macron effect

Much of the investment in French tech predates Macron’s reforms. The state investment bank Bpifrance, launched by former French president François Hollande in 2013, has been widely credited with developing the sector. Hollande also set up new foreign visas for start-up entrepreneurs.

But Zahir Bouchaary, a Briton who works out of Station F, credits Macron with injecting dynamism into the sector.

“Macron has installed a [start-up] mentality within the French ecosystem itself,” said Bouchaary, adding that it has become much easier to do business in France in the last few years.

“French customers are a lot more willing to work with start-ups than they were before,” said Bouchaary. “France was a very conservative country and our clients were used to working with big old-fashioned companies that have been around for a while. For the past few years, they’ve opened up a lot more to working with younger companies and seem to take more risks than they did before.”

Jones agreed that Macron was “the single variable”. “When he [Macron] goes, the dynamism will go too. I absolutely would not expect that to remain the case if he’s not the president.”

However, although Macron has moved to ease labour laws, Jones said that navigating the country’s labyrinthine bureaucracy in French remained “very burdensome”, and that it was far easier to build a business in the UK. “Whether it’s from a tax perspective or from a legal perspective it’s just so much more complicated.”

UK tech ‘resilient’

The tech scene in London appears to be just as vibrant as ever, explained Albin Serviant, president of Frenchtech in London, who said many UK-based tech entrepreneurs are adopting a “wait and see” approach to Brexit.

“The UK ecosystem is quite resilient,” said Serviant.

“In the first quarter of 2019, there were about €2 billion invested in tech in London. That’s compared to 1.5 billion last year, which is plus 30 percent. And that’s twice as much as France – which invested 1 billion. France is catching up very fast but the investment money is still flowing in the UK,” he added.

Serviant cited London’s business-friendly ecosystem and international talent pool as reasons for why London remains the capital of the European tech sector. Barcelona and Berlin are also contenders for the UK’s tech start-up crown.

Nonetheless, Serviant cautioned against the effects that a hard Brexit would have on the tech sector in the UK.

“‘If Brexit happens in a bad way and if people like me and other entrepreneurs have to leave, obviously that’s very bad for the UK because what makes it very different is the international DNA of London.”

Hard Brexit would not just damage the UK tech sector but would also pose challenges for British developers, who post-Brexit may need a carte de séjour to work in the country, looking to find work in France.

Sarah Pedroza, co-managing director of Hello Tomorrow technologies, a Paris-based startup NGO, said that if she had to choose between hiring a British national and an EU citizen with the same skillset, she would opt for an EU citizen because there would be less paperwork involved.

Brexit aside, others suggest that France is snapping at the UK’s technological heels.

“I do think France has the potential under Macron to close the gap with the UK,” said Jones.

“The single biggest factor in what’s going on for France is that France is developing a sense of confidence in itself, in its start-up scene, as a tech hub, that’s being helped by France and that’s also being helped by Brexit.”

The Guardian

Source: Boris Johnson is a clown who has united the EU against Britain | Jean Quatremer | Opinion | The Guardian

Friday 25 November 2016 13.36 GMTLast modified on Friday 25 November 2016 14.36 GMT

Britain can be proud of itself. Once again, it had already shown the world the way. In propelling Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage to triumph on 23 June, it demonstrated well before 8 November that Donald Trump was nothing new.

In fact foolishness, vulgarity, inconsistency, and irresponsibility seem actually to be British inventions that have been painstakingly copied – once more – by the Americans.

The age of such drab characters as Margaret Thatcher and David Cameron is over. No more, it appears, must we suffer leaders equipped with a brain and a sense of the common interest. The hour of the political clown has come.

In a few short weeks, Boris Johnson, the former journalist – for whom facts were never an obstacle likely to get in the way of a good story – has succeeded in squandering what little sympathy and understanding was left in Europe for a Great Britain embroiled in the mess of this referendum.

It is quite some diplomatic achievement to have succeeded in uniting, as never before, the 27 remaining members of the European Union – including Germany and the Netherlands – who are all now firmly together in deciding to do the UK no favours whatsoever.

It will be a “hard Brexit” not because that is what Theresa May wants, but because her future ex-partners consider they have no choice faced with a Great Britain so resolutely indecisive.

Johnson has deeply annoyed his continental partners by displaying, firstly, his complete ignorance of the union (perhaps not altogether surprising if you knew him as a “journalist” in Brussels, as I did). According to his very personal interpretation of the European treaties, it is “bollocks” to say that the four fundamental freedoms (free movement of people, goods, services and capital) are inseparable.

“Everybody now has it in their head that every human being has some fundamental God-given right to move wherever they want,” he said earlier this month.

For Johnson, here there can of course be a “dynamic trade relationship and we will take back control of our borders, but we remain an open and welcoming society”.

Yet the German finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, warned him very clearly as early as September. “We’ll happily send Her Majesty’s foreign minister a copy of the Lisbon treaty,” he said. “He can then read about the fact that there’s a certain connection between the single market and the four freedoms. At a pinch, I can talk about it in English.”

Schäuble reiterated on 18 November that there “will be no à la carte menu. There is only the whole menu or none.” His Dutch colleague Jeroen Dijsselbloem, meanwhile, hammered the message home: Johnson is spouting stuff that is “intellectually impossible” and “politically unachievable”.

Nevertheless, Johnson repeats his mantra ad infinitum: he is right, and the others are all wrong. The problem, however, is that at the end of the day it is the others who will decide. And if you want something from someone, it is generally wiser to avoid telling them they are an idiot.

But the foreign secretary adds clumsiness to ignorance. Johnson – who has, remember, written a biography of Winston Churchill – does not seem to grasp that it takes a mind with a rare degree of finesse to be able to combine humour and diplomacy.

His quip that the Italians would sell less prosecco to Britain if the UK was not able to stay in the single market not only created a diplomatic incident, but underlined the obvious weakness of the British argument: if the EU risks losing access to a market of 64 million Brits, Britain will lose access to a market of 440 million Europeans.

And last but not least, Johnson, who himself raised the spectre of hordes of Turkish citizens arriving in the UK if it stayed in the union, now steps up as as the most ardent defender there is of Ankara joining the EU – even if it reintroduces the death penalty.

“I can no longer respect this,” raged the normally placid Manfred Weber, leader of the conservative EPP group in the European parliament. “When you want to leave a club, you have no say anymore in the long-term future of this club.”

A famous French screenwriter Michel Audiard coined a phrase in the early 1960s that applies perfectly to Johnson: “Les cons, ça ose tout, c’est même à ça qu’on les reconnaît.” This means, roughly: “Fools” (to choose a relatively inoffensive rendering) “will try anything – that’s how you know they’re fools.”

The foreign secretary, who like Trump is no fan of beating about the bush, will pardon my familiarity. Or perhaps not.