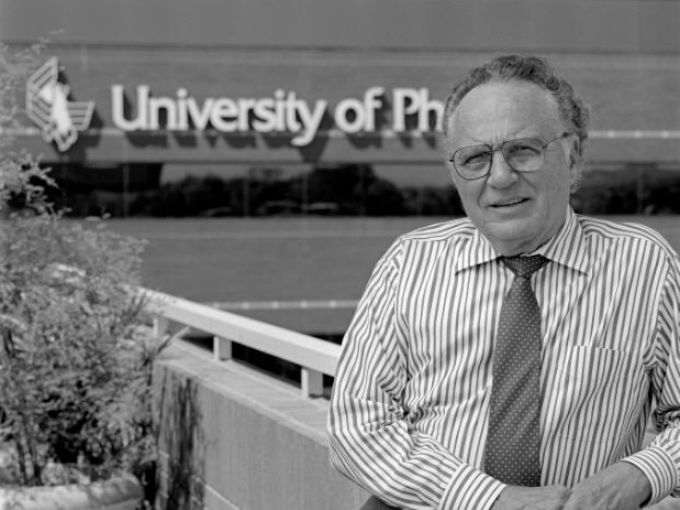

I had the great good fortune to know Professor John Sperling, Cambridge don, when I was an undergraduate student at San Jose State University. At that time, our campus was awash in great thinkers: visiting scholars Buckminster Fuller, Alan Watts, and a host of other eminent faculty. I knew Sperling as a friend and mentor, and worked closely with John and my friends with the SJSU student government: Dick Miner, Peter Ellis and others, some of whom went on to work with Sperling at the Institute of Professional Development and later at the University of Phoenix. My fondest recollection of John was as the catalyst for our symbolic burial of an ugly yellow Ford Maverick on the first Earth Day. John challenged us to define ourselves by what we would do to mark that day. It has become one of the defining events of the first Earth Day. But I also view John as the precursor of the current MOOC’s movement. John shook up the academic world with his revolutionary ideas about education. John created immense controversy but he also spawned significant change. Regrettably, over the years, Phoenix has turned into a questionable “for profit” education mill, akin to Trump University, and now the subject of a federal lawsuit for defrauding military veterans.

From the Arizona Republic:

John Sperling, a virtual illiterate as a teenager, learned to love learning as a young adult and went on to revolutionize the business of college education and access to it by creating the for-profit University of Phoenix.

His death at 93 on Friday was announced Sunday on the website of Apollo Education Group, the University of Phoenix’s parent company. A cause of death was not listed.

Sperling, a billionaire with homes in the San Francisco Bay Area and Phoenix, was remembered for his vision and his tenacity in support of adult education and numerous other causes that engaged his passion. Although he kept a low profile in Arizona, his philanthropy supported a variety of causes, from solar research to anti-aging efforts to the decriminalization of marijuana.

Sperling’s son, Apollo Group Board Chairman Peter Sperling, and company CEO Greg Cappelli said in the statement that “Dr. Sperling’s indomitable ideas and life’s work served as a catalyst for innovations widely accepted as having made higher education more accessible to adult students.”

Sperling founded the chain of schools in the 1970s and retired as executive chairman from its parent company in 2012. On his watch, the school grew from a small California operation to a publicly traded Fortune 500 company with 12,000 workers in Arizona. It established itself as the national leader in adult education and online classes.

Sperling’s schools often catered to older students wanting classes at more flexible hours. By tapping a demographic niche that traditional schools missed or didn’t want, Sperling elbowed the University of Phoenix into a lasting place in the often-staid world of higher education. But by the time he retired, the University of Phoenix had become a sometimes-controversial symbol of the rapid growth and excesses of for-profit universities.

The financial success of the University of Phoenix allowed Sperling to bankroll his social initiatives, from advocating medical marijuana to seeking to clone his dog.

“University of Phoenix is my proudest legacy,” Sperling said in a 2011 interview withThe Republic. “Knowing that over 1million staff, faculty and students have benefited in some way from the university is something I’m very proud of.”

“I think everyone will agree John Sperling really shook up the higher-education world,” said William Tierney, a professor of higher education at the University of Southern California and co-author of the book “New Players, Different Game: Understanding the Rise of For-Profit Colleges and Universities.”

“Sperling realized a need that the market had not thought about and the public sector frankly didn’t care about, and man, was he right,” Tierney said in a 2013 interview. “He really tapped into education as a needed commodity in a way that nobody else had done.”

A singular vision

Those who knew him well described Sperling as a man of generosity, curiosity, vision and grit.

“His focus was on bettering people’s lives,” said Jorge Klor de Alva, a former University of Phoenix president and Apollo Group senior vice president who knew Sperling for more than 40 years. “This university was focused on trying to help people succeed.”

Klor de Alva said Sperling, essentially shy, never backed down from a fight.

“He was always in pursuit of social-justice causes,” Klor de Alva said.

Grant Woods, a former Arizona attorney general and attorney who represented Apollo Education Group, said Sperling was ahead of his time with his views on many topics, including treatment for drug offenders, instead of incarceration, and the benefits of telemedicine.

“Professionally I was impressed with how visionary he was,” Woods said. “He was willing to be controversial, to fight the fights that most people wouldn’t fight. He was never afraid to put his money and his prestige behind them.”

Sperling invested heavily into causes including plant genetics and seawater agriculture, anti-aging medicine and drug decriminalization as opposed to treatment. He participated in efforts with fellow billionaires George Soros and Peter Lewis to sponsor and pass citizen-backed initiatives in 17 states focusing on treatment and education, as opposed to jail time, for non-violent offenders, while decriminalizing marijuana, especially for medical purposes.

U.S. House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, a fellow Bay area resident, said in a statement: “John Sperling’s passion for education changed America. By improving access to higher education for thousands of non-traditional students, he created a movement and empowered a generation of working adults with the tools needed to provide a better quality of life for their families. His life story inspires us to see — and seize — opportunities.”

Humble beginnings

Sperling achieved his perch atop for-profit education after escaping a humble, sickly and unhappy childhood.

In his autobiography, “Rebel With a Cause,” Sperling wrote that he was the youngest of five children. He was born in a log cabin in Missouri and raised in a home that had a coal-burning stove and an outhouse. He said his mother was “possessively loving” and described his father as a “classic ne’er-do-well” who often beat him.

“I learned nothing from my childhood except that it’s a mean world out there, and you’ve got to bite and scratch to get by,” he told Fast Company in a 2003 interview.

Sperling joined the Merchant Marine in 1939, and one of his ship’s engineers befriended him, teaching Sperling to read. Sperling was spellbound by classics such as “Notes from the Underground” and “The Great Gatsby,” fueling a lifelong love of literature and poetry.

After serving in the U.S. Army Air Corps, Sperling earned an undergraduate degree from Reed College on the G.I. Bill. He then attended the University of California-Berkeley, where he was awarded a fellowship to study at King’s College at the University of Cambridge. He earned his doctorate in 18th-century English mercantile history in 1955.

Starting in 1960, Sperling served for 12 years as a tenured professor of history at San Jose State University.

There, Sperling made a name as a union activist.

Popular program

While still teaching in San Jose, in 1974 Sperling won a government contract to develop coursework for teachers and police officers who worked with at-risk children.

According to New Yorker magazine, top administrators at San Jose State balked at the program. The University of San Francisco was more receptive, so he launched it there.

The program proved so popular that Sperling, working with business partners, created an adult-education program for 2,500 students with classes available at Bay Area colleges. It became known as the Institute for Professional Development and offered bachelor’s and master’s degrees for its students.

“He got this thing going, and it was making money. It was running a surplus,” said David Breneman, a University of Virginia professor who teaches the economics of education. “The regional accrediting body in California came down on him like a ton of bricks. They didn’t like anything he was doing.”

Sperling responded in 1976 by moving the IPD and renaming it after its new home: the University of Phoenix. Within three years, it gained grudging accreditation in Arizona.

Sperling told The Republic that Arizona attracted him because the state “had never gotten around to writing any regulations.”

With his background in economics, Sperling draped his university in pragmatic cost-consciousness. Instructors were drawn from the working world. Accountants, for example, taught accounting rather than decorated academics.

Students presumably benefited from the instructors’ real-world experience; Sperling and the students gained from the lower faculty salaries that went with it.

In 1981, Sperling formed the Apollo Group, the parent company of the university, and bought out one of his partners. Seven years later, Sperling bought out another partner to take full control of Apollo.

As the university fell under his full control, it also began developing distance-learning classes, a forerunner to the online courses that would help remake adult education.

For years, the University of Phoenix grew steadily, largely on the strength of an older student body looking to start new careers. At a time when traditional schools made students build schedules around faculty, Sperling built his no-frills school around the students.

In December 1994, the Apollo Group joined the Nasdaq Stock Market as a publicly traded company. At the time, it had 28,000 students. In some ways, it was a final vindication of Sperling’s unique approach to higher education. But some say it also put the school on a new path that inevitably led to a shift in priorities.

“They got pushed by Wall Street,” said Breneman, who co-edited the book “Earnings from Learning: The Rise of For-Profit Universities.” “They got into this rat race of having to try to grow 10, 20, 30percent every year, so they started dipping down into younger students.”

By 2000, enrollment in the Apollo Group’s holdings reached 100,000. Three years later, it was 200,000. By 2010, enrollment had mushroomed to 600,000.

At that point, more than 80 percent of the university’s revenue source was federally backed student loans. In 2008, for example, it collected more than $3billion in federal financial aid.

That attracted scrutiny from Washington. On Capitol Hill, the university and its many for-profit competitors came under fire for bringing in too many students ill-prepared for college who, if they graduated at all, found themselves saddled with high debt and poor job prospects. The high dropout rates were fueled, some said, by recruiters whose pay was effectively tied to enrollment, which would violate federal law.

In 2009, the Apollo Group settled a whistle-blower lawsuit against the university for nearly $80million to dispense with claims of recruiting commissions.

A two-year Senate investigation pointed out in 2012 that an online degree from the University of Phoenix cost six times more than a comparable degree from the Maricopa Community College system and that Sperling was paid $8.6million in 2009, 13 times more than the president of the University of Arizona.

“When the University of Phoenix was started in 1976, it pioneered an entirely new model of learning,” the report concluded. “That model revolutionized thinking about how to provide opportunities for higher education to underserved and non-traditional students. Yet in the 2000s, Apollo appears to have made critical decisions that prioritized financial success over student success.”

During the probe, Washington tightened lending rules to hold schools accountable for the degrees their students pursued, and the university made its own adjustments, though Sperling, with characteristic bluntness, disagreed.

“We don’t agree with the new regulations. We think they are stupid,” he told The Republic in 2011.

Operating under tighter regulations, an uncertain economy and intense competition from other for-profit schools and public universities that had learned from Sperling’s model, the University of Phoenix contracted. It has cut its payrolls by thousands, and degreed enrollment in May was 242,000.

Sperling left as CEO of the Apollo Group in 2001 and retired as executive chairman of the company’s board of directors in December 2012.

Variety of causes

In 1996, Sperling gained attention as a financial backer of medical marijuana in Arizona, something he favored during his recovery from prostate cancer in the late 1970s.

In 2000, he funded a biotech company to help clone pets. His dog Missy died in 2002 without success in cloning her. Four years later, the company was shuttered.

Between 1997 and 2013, Sperling made more than $700,000 in political contributions, according to federal records. Overwhelmingly, but not totally, he gave to Democrats. He wrote several books, some on education and one outlining his liberal views on political demographics.

Although he was often at odds with the establishment, most say Sperling left a mark on higher education.

“I think we need to give credit where credit is due,” Tierney said. “There are a lot of others out there, and they didn’t become the University of Phoenix. He had an American kind of can-do spirit.”

Sperling is survived by his longtime companion, Joan Hawthorne; his former wife, Virginia Sperling; his son, Peter; his daughter-in-law, Stephanie; and his two grandchildren, Max and Eve.