Perhaps the premiere of Season 4 of “Silicon Valley” twigged me to share this post. but despite the title, the HBO series only connection may be the now viral “mean jerk time algorithm.” The real “Silicon Valley jerk” has been around for decades, buried with all the other dirty laundry. Uber’s Travis Kalanick has only brought it front and center at this moment. It is something of a conundrum as some of the jerks are also the most successful. We all now know about the “bad” Steve Jobs. Oracle for years had a very bad reputation that came directly from Larry Ellison himself. Microsoft was long known as a “sweatshop” with a highly negative culture led by Steve Ballmer. Even venture capitalists themselves have caught the disease as evidenced by Reid Hoffman and the late Tom Perkins of KPCB. The best assessment I have heard is that these aggressive unrestrained corporate cultures destroy their own goals. Or better yet, the saying that “culture trumps strategy.”

Reblogged from the New York Times

The tech industry has a problem with “bro culture.” People have been complaining about it for years. Yet nobody has done much to fix it.

That may finally change if the people in charge of Silicon Valley — venture capitalists, who control the money — start to realize that the real problem with tech bros is not just that they’re boorish jerks. It’s that they’re boorish jerks who don’t know how to run companies.

Look at Uber, the ride-hailing start-up. It’s the biggest tech unicorn in the world, with a valuation of $69 billion. Not long ago Uber seemed invincible. Now it’s in free fall, and top executives have fled. The company’s woes spring entirely from its toxic bro culture, created by its chief executive, Travis Kalanick.

What is bro culture? Basically, a world that favors young men at the expense of everyone else. A “bro co.” has a “bro” C.E.O., or C.E.-Bro, usually a young man who has little work experience but is good-looking, cocky and slightly amoral — a hustler. Instead of being forced by investors to surround himself with seasoned executives, he is left to make decisions on his own.

The bro C.E.O. does what you’d expect an immature young man to do when you give him lots of money and surround him with fawning admirers — he creates a culture built on reckless spending and excessive partying, where bad behavior is not just tolerated but even encouraged. He creates the kind of company in which going to an escort bar with your colleagues, as Mr. Kalanick did in South Korea in 2014, according to recent reports, seems like a good idea. (The visit led, understandably, to a complaint to the personnel department.)

Bro cos. become corporate frat houses, where employees are chosen like pledges, based on “culture fit.” Women get hired, but they rarely get promoted and sometimes complain of being harassed. Minorities and older workers are excluded.

Bro culture also values speedy growth over sustainable profits, and encourages cutting corners, ignoring regulations and doing whatever it takes to win.

Sometimes it works. But often the whole thing just flames out. The bros blow through the money and find they have no viable business. For example, Quirky, founded in 2009 by the 20-something Ben Kaufman. It raised $185 million to build a “social product development platform” that sold kooky gadgets but filed for bankruptcy basically because the “brash” and “unorthodox” chief executive had no business being a chief executive. One indication that Mr. Kaufman is a bro? Well, the first reference he lists on his LinkedIn page is: “He’s a dick … but hilarious.”

Zenefits, a human-resources start-up, and another bro co., raised $583 million, at a peak valuation of $4.5 billion, then crashed after reports that it had used software to cheat on licensing courses for insurance brokers, and operated a hard-partying workplace where cups of beer and used condoms were left in stairwells. Zenefits limps on, but its C.E.-Bro co-founder has left the company, and nearly half the staff has been laid off.

Uber’s public downfall began in February, when Susan Fowler, a former engineer at the company, wrote about enduring sexual harassment and discrimination there. Other employees came forward with stories. One involved a manager groping employees’ breasts. Mr. Kalanick’s own bro-hood became part of the story when a video surfaced showing him berating a Uber driver who complained that Uber’s price cuts had driven him into bankruptcy. Mr. Kalanick said the driver needed to take responsibility for his own life.

As this was happening, Google’s self-driving car unit sued Uber, alleging it had stolen its ideas. Then word leaked that Uber had been using a sneaky software tool to deceive regulators in cities around the world. All this is as much a part of “bro culture” as the poor treatment of women; the point is to get away with as much as you can.

Hoping to right the ship, Uber appointed one of its board members, Arianna Huffington, to join former attorney general Eric Holder and others to investigate the sexual harassment claims. Mr. Kalanick has apologized and vowed to “grow up.” (He’s 40.) Most important, Uber has announced that it is planning to hire a chief operating officer, ideally a steady hand like Sheryl Sandberg, the chief operating officer of Facebook. It’s a great idea, but it should have happened years ago. Now it may be too late.

Ms. Huffington insists the board has full confidence in Mr. Kalanick. But should it? He’s a college dropout with a spotty track record and a reputation for pugnacity. His record at Uber includes racking up enormous losses — reportedly $5 billion over the last two years. Despite this, the bluest blue-chip investors (including Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley) have invested a total of $16 billion in Uber.

Bro C.E.O.s are better at raising money than making money. So why do venture capitalists keep investing in them? It may be because many of the venture capitalists are bros as well.

Venture capitalists used to be tech engineers who had made a bundle, retired early and took up investing in start-ups as a kind of white-shoe hobby. The new breed are competitive alpha males who previously might have gone to work as bond traders. At the same time, there are fewer women. In 1999, 10 percent of investing partners at venture capital companies were women. By 2014 the number had declined to 6 percent, according to the Diana Project at Babson College. This is probably one reason that, despite many studies showing that women run companies better than men, none of the 15 biggest American tech companies valued over $1 billion has a female chief executive.

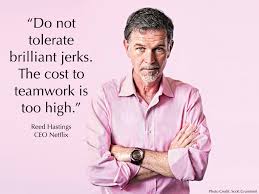

Uber’s collapse should not come as a surprise but it does offer a lesson: Toxic workplace culture and rotten financial performance go hand-in-hand. It’s possible for a boorish jerk to run a successful company, but jerks do best when surrounded by non-jerks, and bros do best when they hire seasoned executives to help them. Without “adult supervision” and institutional restraints, the C.E.-Bro’s vices end up infecting the culture of the workplaces they control.

This poisonous state of affairs will get fixed only when investors start getting hurt. A crash at Uber, the most high-profile tech start-up in the world, could provide the jolt that finally brings the tech industry back to its senses.

Graham says well-known founders like Jobs and Bezos can’t be judged by their terror tales. “Famous founders who seem to be –holes might not be,” Graham told Business Insider via email. “I’m not saying they are or they aren’t, just that it is extremely hard to tell what a famous person is really like. You can’t judge them based on anecdotal evidence, which is all you ever have.”

Graham says well-known founders like Jobs and Bezos can’t be judged by their terror tales. “Famous founders who seem to be –holes might not be,” Graham told Business Insider via email. “I’m not saying they are or they aren’t, just that it is extremely hard to tell what a famous person is really like. You can’t judge them based on anecdotal evidence, which is all you ever have.”

BY

BY